One of the emotionally complicating factors of constantly living in and travelling through countries with troubled pasts is that you will inevitably end up having many conversations with and interacting with people who had lived through that troubled past.

And given that troubled pasts often involved death, betrayal, torture, imprisonment and whatnot, it’s a disconcerting feeling wondering which side the guy selling you a beer was on.

Or whether your student had any immediate family members or friends tortured and imprisoned (which happened in Turkey a few times, including once with a middle-aged business student casually mentioning that his father’s three best friends were executed for being communists after the military coup thirty years ago).

Or whether the sweet middle aged Chinese dorm mother you work with daily ever betrayed her parents as a Red Guard, or if she had been pulled out of school to farm millet for her teen years, or if her family had starved to death during the famines after the Great Leap Forward.

(Side note: I’ll probably get myself on the Great Firewall’s bad list for this one. Too many key words. Damn.)

In Cambodia, I kind of knew which side most of the people were on, since the Khmer Rouge pretty much destroyed the country and its people quite thoroughly before finally being run out of town. So I started wondering about all the kind, smiling people we met: the tuktuk drivers, the waitstaff, the guides, the construction workers, the hotel staff, the armless and legless land-mined book sellers on the streets, the children running after you keening out a phoenetic approximation of monnaieeeeeee monnnnaiiiieee.

I’m making these photos big, by the way, so they can be seen clearly and immediately. They will be wider than the parameters my theme gives me. This is intentional.

I don’t want small pictures here.

You know that everyone had been screwed over, whether directly or indirectly. It has been pretty hard to be Cambodian in the past 50 years and have not had a rather rough time (to put it mildly). I read somewhere that Post Traumatic Stress Disorder levels ranged from 50% to 80%, depending on how it was defined. The genocide took place between 1975 and 1979. I’m 36. I was born in 1974.

If I had been born Cambodian, my family and I would have definitely been murdered: we are full of teachers and educated folk, city dwellers mostly.

As a baby, it would not have been inconceivable that I would have been murdered alongside my mother. In the museum, I saw a portrait of a young mother holding her baby before being tortured and murdered. Both of them. The baby was tortured and murdered too. It was their mug shot. The Khmer Rouge were very meticulous in their documentation: mug shots just after arrest, shots after torture, shots upon death.

I want to show you some photos I took one day in Phnom Penh.

We went to the Genocide Museum first, as it’s in town, in a former school. AKA Tuol Sleng S21. It was a Khmer Rouge prison. They tortured and killed more than 20,000 people there during the Pol Pot years in the mid-late 1970s. A school.

A freaking school.

The classrooms were used as prison cells. There are torture instruments still in the classrooms.

There is barbed wire across the balconies that run past all the classrooms on the upper floors so people wouldn’t be able to escape by jumping.

There are monkey bars in the playground that were re-purposed for lynching.

There are graves in the playground, holding the last remaining corpses found after it was liberated. Seven people survived.

As a teacher, this horrifies me even more than it ought to.

Here is a classroom that was divided into a dozen tiny cells. There are shackles still nailed to the floor.

I walked around the school grounds, mostly separate from Doug and his parents. It was a museum I could only process in solitude.

My inner inappropriate macabre self noted the mops in the stairwell and I took a picture of them because, well, mops are my thing.

Even mops in a fucking torture chamber. In a prison.

I didn’t have a guide, though I probably ought to have hired one for depth of understanding. Apparently the guides there have first hand knowledge of what went on there. Apparently no one wants this job. The job involves reliving an appalling, horrifying past on an hourly basis. There are guides there though.

I saw a guide look away as a young American girl burst into tears when shown the monkey bars where people were tortured.

We never usually think of monkey bars as instruments of torture. It fucks with your head to know that others did.

Across the street from the walled (reinforced by barbed wire) school/prison are a dozen waiting tour buses, another two dozen tuk tuks, and a lot of souvenir shops. Some are charitable. Some are just souvenir shops.

I bought a courier bag and a purse made of newspaper that had been laminated then sewn into bag shapes. This was an NGO operation to assist women impacted by, well, being Cambodian. They are excellent bags. I recommend getting one if you’re ever in the neighbourhood.

There are also few small restaurants and cafes, a backpacker hostel. Across from a place of genocide. It’s an uncomfortable juxtaposition for me.

After this, we went to the Killing Fields. I knew about the Killing Fields. I had seen the movie; I had seen Swimming to Cambodia several times, compulsively, since I was 15. I had read up on the Khmer Rouge. I had read a lot. I’m a history nerd. I have a BA in revolutionary Chinese history with a minor in every other country in the past hundred years who did appalling things to its people (not a lucrative field, I can tell you that- and it comes with an awareness is not an easy thing to possess).

I want to show you something.

I find it very disturbing to think about people without heads. We are supposed to have heads: it is part of who we are. And yet here, in the Killing Fields, the first mass grave I came upon was for the headless. I felt ill.

But that wasn’t the first thing I saw. Let me show you what everyone sees when they first arrive (aside from the armless/legless beggars pleading for alms at the entrance gate).

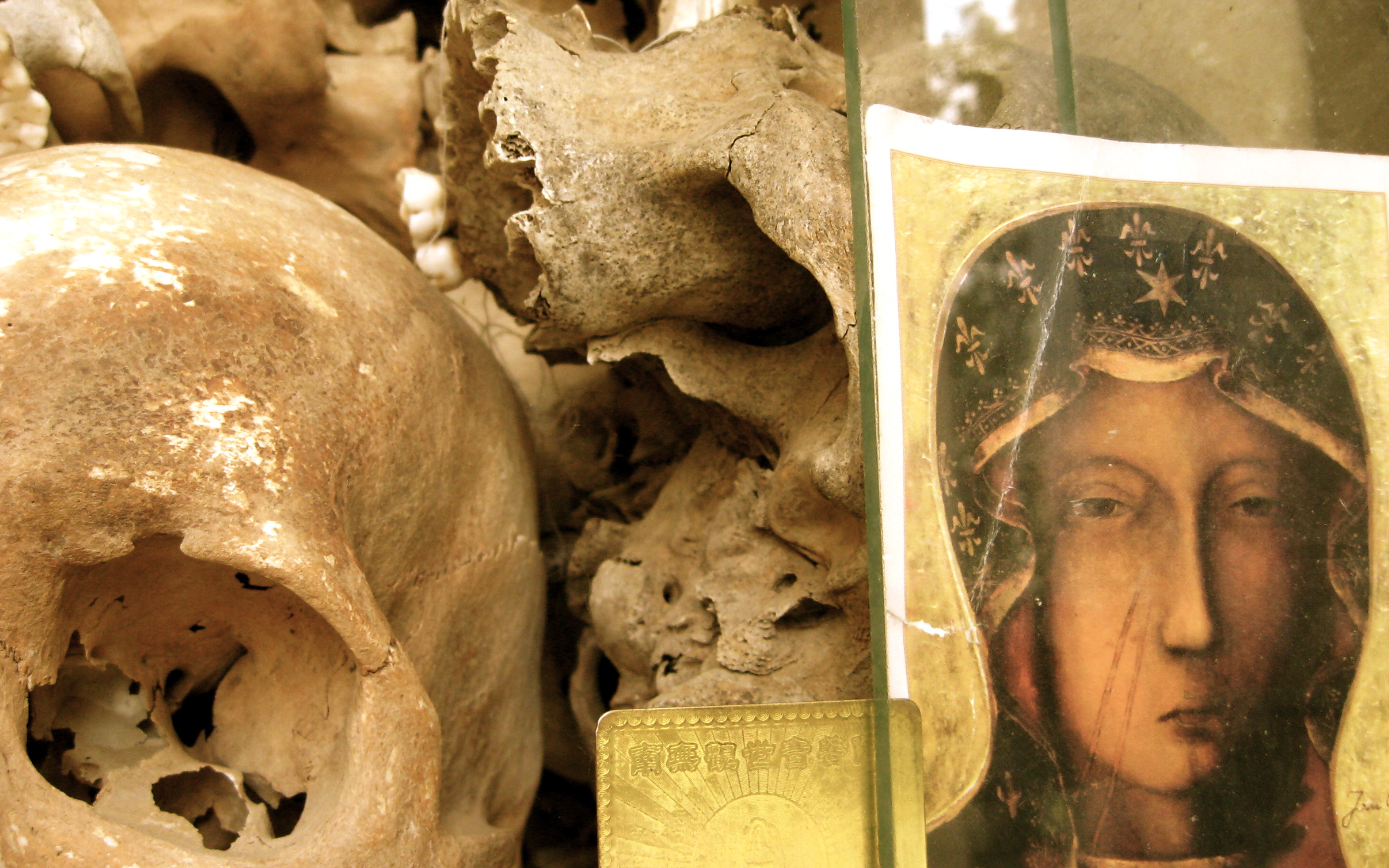

Shall I give you a close up for full impact, so you don’t just scroll down quickly without realizing that you are scrolling past the skulls (and proof of murder) of hundreds of people, primarily artists, writers, teachers, professors, city dwellers—- folk like most of us who are reading this (or writing this)?

I want to show you some other things.

After the Genocide Museum and the Killing Fields, we tuk-tuk’d back into town and, well, had dinner and a few cocktails and went back to our rather pleasant hotel room (the one with a private pool) and slept soundly. Because we could. Because no one was trying to murder us or our families.

Let’s just stop a moment and think about this.

We are lucky. We are blessed. Our families (I hope) are not methodically imprisoned and murdered. If we travel, we are blessed. Our lives are fortunate.

We must not forget how amazingly fortunate we are.

Because we are.

27 Responses

I’ll come right out and say that I’m not as brave as you. Though I have traveled extensively, I’ve avoided places where Bad Things Happened, partially out of circumstance and partially out of cowardice.

Then there’s Zimbabwe.

I’ve been there twice, once when things were teetering on the verge but before everything really went to hell (July 2000) and once years later, after the dust had settled (February 2007). The decay was obvious and visible, as was the desperation, and the knowledge that everybody here–everybody–either knew somebody who was murdered, starved, or tortured. I sat with Zimbabwean students while they watched their worlds fall apart and listened to the phone calls of distant cousins to the secretary of the department at the university, where no words were ever spoken in an intricate dance of begging for a safe haven and offering a place to stay.

Just like Cambodia, or Uganda for that matter, the educated were driven out, exiled, imprisoned, tortured, or executed. The educated will disagree, and are less likely to be ruled by terror. That was particularly difficult in Zim as the country had made a long push for high-quality education; after South Africa and Egypt it had the third highest literacy rate and percentage of people with post-secondary education on the continent. Not all of them were the stereotypical white farmers–some were South Africans living in exile, some were Shona or Matabele. In a cruel twist of irony, the well-educated white people were able to flee (many to Zambia and Mozambique, who realized that these people could be a major asset to their nations), while the black people were murdered. So when I took my parents there, it wasn’t without major reservations and deliberation. I didn’t want any of my money to go to the government, I didn’t want to put my elderly parents into a bad situation. We went anyway, and I made sure that we had a week in South Africa beforehand and a day trip to Botswana…just so they could see the other side. Two things stuck out at us–cows and shoes.

I’m not a farmgirl, but I recognize high quality, well-bred livestock who are well fed and in good condition. The cows in Botswana were well-grown, in good flesh, with bright eyes and good coats. The cows just across the Chobe river were smaller, less massive, and while healthy from good grazing did not compare in quality. I pointed it out to my father, and said, these are the culls from Botswana. After the famine, when all the cattle would have been eaten, the poorest of the herds would have been sent across the river.

Requiring less of an eye, of course, was the fact that everybody in Botswana save the very young and very old wore good shoes in good condition. In Zim, they were either barefoot or wearing shoes patched and resoled as best as possible.

Yes. As someone closely associated with Zim and SA in during the turn of the century (1997-2000 for me) I agree. There was so much going on there that I can’t even begin to talk about it. I was with a lovely non-racist and thoughtful (white, Afrikaner) South African for several years, while at the same time working with, living amongst Zim and SA people who who, um, weren’t white. Most of the nurses worked with between 1997-2000 were Zimbabwean. And Eritrean. And Ethiopian. 99% of the staff in London old-age care homes were African. My flatmates in London in 1997 were three Zimbabwean white fellas escaping the crashing Zim dollar (50 to the UK pound at that point). Everyone I lived with was a self declared white refugee. There were a few African ZImbabweans I knew through my nursing job in London but most were white. Everything was very, very complicated. I knew.

There was so much going on there at that time that I can’t even begin to articulate it.

I look at what’s going on in the mideast at the moment, and the overwhelming thought in my head is–this is the last vestiges of the cold war, writ large. Governments of 30-40 years, installed in the late 70s to early 80s because they were for one side or against the other, are finally falling. It happened more or less of its own accord in South America in the 1990s, in central/west Africa in the 00s, and now in the teens in the mideast. Good RIDDANCE.

So, by extension, I look at what happened in Zim between 1995-2007 to be the the necessary consequence of the fall of the apartheid government. Suddenly, a country which had held a LOT of regional power and prestige was eclipsed by its larger, stronger, better-educated, more industrialized neighbour. Excesses that might have been permitted when the apartheid government was still in power came under harsher light than previous, and old debts had to be paid. As much as it was a tragedy for the landowner-farmers, who (in spite of/because of everything else) were a strong and enduring professional class, it was more of a tragedy for the workers who depended on them and by and large were killed, maimed, or tortured. I damn near danced for joy when the one farmer who filed a racism claim at the human rights commission won, as it exposed the claim that black zimbabweans were being given land to farm for the lie that it was, and revealed it as the ugly power grab anybody with half a brain could see.

It’s very easy to sit here from the comfortable desk of my norwegian-owned, british-operated, bahamian-flagged ship where the vast majority of people of colour on board are working as galley hands and cabin stewards and deck monkeys (and they work HARD and are GOOD at what they do–I’d rather have a filipino deckhand than some good ol’boy any day of the week) and judge. Just–time and distance give a lens through which it’s easy to see what happened, even if solutions were/are impossible.

We are indeed lucky…..it’s inadequate but still the only word appropriate for our winning t

the Birth place lottery….. Strong piece, bought back slot of memories. I was over there covering the ECCC trials in 2009 and sitting in the hot courtroom looking at Duch, an old man now who was in charge of Toul Sleng, it was difficult to reconcile his calm and apologetic demeanor with the crimes he is charged with.

You saw Duch? I don’t know if I could handle that. Cambodia was harder on me than I’d expected (monkey bite excepted).

i think its sick no-one deserves to be treated like this :(xx

I have no words, just tears.

I saw all of that a few years ago and it was just as awful and horrifying to think about then as it is to look at the pictures and think about it now. I went to the prison with a friend and we had to leave because it was so upsetting–I’ve never been in a place where I felt ghosts (and I don’t even really believe in them) as much as I did there. Just awful. It was kind of like seeing the concentration camps in Germany–what hit me the hardest was the ditches they had dug so when they shot people it would be easily cleaned up. There’s a lot of horror in the world that we are, as you’ve said, lucky not to have to live through. Thanks for the reminder.

Indeed. The truth is – no matter where we roam, nor what poor (armless/blind/leprous) soul we meet or remember… There but for the sheer luck (or unluck) of the draw – go we. Be it the skeletal mother trying to feed her pot-bellied starving children in a thatched hut in Africa, or the the poor souls who perished hideously from the likes of Pol Pot. It could just as easily have been you or me. Your grandmother, father, sister, son.

In all of my travels (indeed, a large part of WHY I travel) I am ever reminded/mindful of the simple fact that: I just HAPPENED to be born to the kind couple of Bill and Arleen, from Oak Park Illinois (and thus, have both a precious U.S. passport, along with the education and means to skip about the globe). But I could JUST AS EASILY have been born to that skeletal mother in a thatched hut…

Thankful. Supremely grateful. Ever compassionate. Not to mention, a stark reminder why we have verily NOTHING to ever WHINE about!

I agree 100% and couldn’t have said it any better.

I knew I couldn’t handle the day tour combining the genocide museum and the Killing Fields so I decided to just do Tuol Sleng instead. I was in tears for the most part. It’s absolutely astounding how much torture and inhumanity human beings are capable of.

These places of torture are difficult to deal with and of course no one wants to be confronted with such horrors, but I think they serve as a very important reminder of what hate can breed in people.

We are all very lucky to have never had to experience such atrocities first-hand, but the sad reality is that not everyone was so lucky. I think part of why it’s important to confront and face these events, no matter how far removed from it we may have been due to location, status or time period, is to honor and remember those who didn’t survive and to use that as a means to help ensure it doesn’t happen again. If we ignore or forget what happened, then the victims truly would have died in vain.

It was hard to visit both places in one day but I wanted to see the path that people were forced to follow, from prison to execution. It’s a grim path but it was worth it for the impact. It’s so important to remind ourselves of how VERY lucky we are and how unlucky others have been. It’s easy to forget.

Wow, MaryAnne. I don’t really know what to say. Super-powerful post. I haven’t made it to Cambodia yet, am dying to, but at the same time fairly certain I’d just be a blubbering mess the whole time.

Even more poignant and disturbing and depressing when you think about what’s happening in Libya right now, and how torture and disappearance and assassination are still, apparently, seen as legitimate political tools by leaders in plenty of other countries, as well.

Thanks so much for writing this and sharing the photos.

Thank you for your comment, Camden. This was a HARD post to write. Took most of a day- a very unhappy day. It felt necessary to write, especially since I’m living in China, now that anything to do with the events in the Middle East have been totally blocked for fear of…well, reminding people that horrible things still happen.

As for Cambodia as a whole, in spite of everything that has happened there, on the surface it’s a very pleasant, calm place. I wish i could grasp what goes on beneath that poised, pleasant Buddhist demeanour. If they are traumatized, they mask it very well. I think a lot of tourists there don’t quite realize the depth of the situation, esp those in beach towns like Sihanoukville. I came across backpackers there who were so clueless and insensitive that i just wanted to punch them.

How shocking. I remember feeling this way while visiting the Holocaust Museum in Israel. It really does a number on the soul to think that people treated each other so inhumanely. Wonderful and educational post. Thank you! Look forward to reading more.

Thank you. It was a tough post to write. I look forward to your return- all comments are welcomed!

Truly terrible. I had a friend growing up whose parents escaped the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. Her stories were always so heart-breaking and more real to me. Very powerful post here.

Thanks, Suzy. I find it so hard to fathom what it must be like to go through something so indescribably awful.

Interesting post, I really enjoyed reading it and it brought some perspective to my studies.

I’m working on a Masters in History and focusing on Genocide Studies and as I examine more and more cases of genocide, it becomes easy to look at the hundreds of thousands (and even millions) killed as “so many statistics.” This genocide is more “popular” than that – some genocides are rarely studied or even acknowledged (Tibet for example) while others are given their own names to segregate them from the rest (Holocaust vs. Genocide).

As I look through the history of the 20th Century and the centuries before, it seems that man has been killing man and as resources (and land) dwindle, mass killing of people becomes the way to wage “total war” on the people rather than just the army. Genocide has been around for a long time: God commanded the Israelites to slay those in the Promised Land lest they corrupt the Hebrews with their pagan religions (kill the men, women AND children, even the oxen & knock down all the buildings), Shakka Zulu practiced genocide against his foes as did Chenggis Khan (but only if they didn’t surrender).

After the fall of the wall in Germany, we are getting a look at the Soviet archives and we find that Hitler was small potatoes compared to Stalin who killed (at least) 7 million in Ukraine in one year, possibly double that number.

I’ve been to Auschwitz/Birkenau in Poland and to Dachau in Germany. On my next trip to Belarus I’ll visit the killing fields at Kurapaty just outside of Minsk. I did not see this location during my visit to Cambodia and I wish that I had.

And in reading this post, it reminds me of my visits to Holocaust concentration camps and puts a face – a human story to the suffering that – when studying mass murder – become easily obscured in large numbers with many commas of the number of victims…

Hi Scott, I’m glad this post was of some use. As I mentioned above, I did my undergrad degree in History and people’s awfulness to each other was one of my…um…areas of interest. This has made my travels from the past decade and a half more emotionally complicated than it might be for someone who didn’t know about secret (and not so secret) brutal pasts. It’s so important to move beyond just dry stats in a book and to remember, vividly, with names AND faces, what has happened and what continues to happen.

That was hard to read, and must have been hard to write as well, but thank you for doing it. I’m woefully ignorant about the details of many of the terrible things that have occurred around the world, especially in Asia, but the latest round of reports about mass graves in Turkey certainly has me more keenly attuned to similar tragedies elsewhere. I just finished reading a sad and lovely novel, “Anil’s Ghost,” about a woman investigating political murders in Sri Lanka — another place that hadn’t really been on my radar before.

Your experience brings to mind the visit I made to Dachau on my first trip out of the US. It was a lot for my then-23-year-old mind to handle, even though the Holocaust is so much better taught in American schools than any other genocides. What chilled me most was how methodical it all was — the blueprints handed down from headquarters dictating in detail everything from prisoners’ uniforms to the layout of the rooms, the complicated system of arm-badge identifications. And how ordinary-seeming the place was, just like the ones you described.

A great read, thanks for sharing. We found this from Suzy Guese’s site. We were there not so long ago and felt exactly as you did. Powerful places, unforgettable atrocities.

Here is our photo diary from that day… (two days are covered in the post, killing fields are on the second day) http://www.notworkrelated.co.uk/2011/02/phnom-penh-cambodia-28th-29th-jan/

Keep up the great work in Shanghai 🙂

Regards David and Helen. x

I think my heart just got ripped out of my body. Oh God, it’s so sad.

I went to the Dachau concentration camp in Germany once, and had to try so hard to hold back tears when walking through what used to be the “ovens”. My mind simply can’t wrap itself around how we’re capable of doing this to one another.

These museums exist, so that we can remember these people. So that their lives mean SOMETHING – and hopefully, hopefully, we’ll learn humility, tolerance, compassion from knowing about these ferocious atrocities that no one should EVER have to live through.

It’s heartbreaking. I find it really hard sometimes travelling with awareness of what has gone on in the past. I know that this knowledge and memory is vital but it does make so many places much more painful to visit. This summer? Sri Lanka. I have a feeling I’ll be blurting out a similar post for that as well.

I had an extremely hard time building up the courage to go to Cambodia – until pretty much the last moment I was unsure if I could handle it… On top of staggering awareness of an entire nation’s irreparably broken fate – something that I can relate to on a more personal level, my grandparents having barely survived the horrible artificial famines in Ukraine circa 1932, 1933 and 1937 – it required overcoming one of my biggest childhood traumas/phobias.

My dad is an amputee and since early age I had nightmares about lost limbs, my own or those of people I cared for. Apparently a boy I met in Siem Reap who lost a leg to a landmine “lucked out” comparing to those children who encountered the killing tree executioners, but it was him and other living amputees who made me simply die inside several times…

I hear you! The world– and the history of the world– is so full of horrible things that it can be hard facing the aftermath of it all. Thanks for commenting- I appreciated the connection with the Ukrainian famines. It’s all connected, isn’t it?

I think genocide is sick and no-one should be treated in that way 🙁 xx